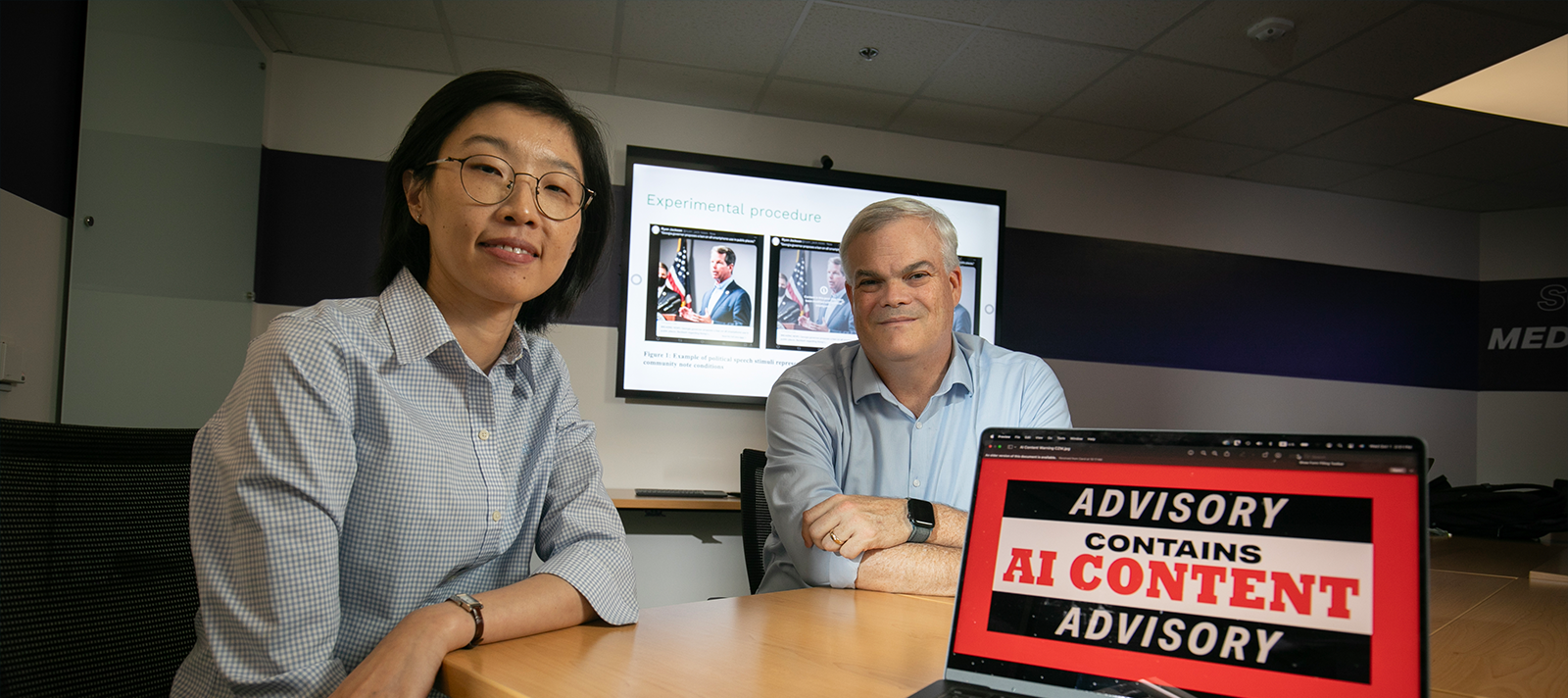

Jie “Jackie” Zhuang researches the role artificial intelligence plays in health care, while Daxton “Chip” Stewart examines the First Amendment issues that arise with efforts to regulate AI-generated content. Photo by Rodger Mallison

How AI Deepfakes and Bias Threaten Elections, Health Care and Public Trust

TCU researchers expose how artificial intelligence is spreading political misinformation, worsening medical disparities and eroding confidence in institutions.

MIDTOWN MANHATTAN’S EQUITABLE CENTER. MAY 1997. Garry Kasparov, world chess champion, faces Deep Blue, an IBM supercomputer capable of evaluating 200 million board positions per second.

They clashed 15 months earlier in Philadelphia, with Kasparov rallying to win 4-2. This time the machine holds the upper hand, becoming the first computer system to defeat a reigning international champion.

“Garry prepared to play against a computer,” said IBM’s C.J. Tan at the time. “But we programmed it to play like a grandmaster.”

In the years since, artificial intelligence has matured from curiosity to ubiquity: Playlists anticipate tastes, and maps reroute around traffic. Generative AI produces essays, images, videos and code with instant fluency.

Yet the foundation of artificial intelligence rests on imbalance. The highest-performing models often train on English or Mandarin sources. “Because those are the large languages, they’re very popular and have a lot of materials online,” said Bingyang Wei, department chair and associate professor of computer science. “But what about the small languages? … What about the cultures that have been left out?”

These gaps determine who benefits from technology and who is shut out, sometimes with life-or-death consequences.

As AI increasingly shapes the world and its inhabitants, TCU scholars are studying it as a powerful actor affecting everything from politics to health care to crisis communication.

As AI permeates modern society, humans are harnessing its benefits and grappling with the perils of its misuse. TOONS17 | ISTOCKPHOTO

DEEPFAKES AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT

The rise of AI-generated content has presented new legal challenges, particularly to political speech. In 2024, First Amendment and media law scholar Daxton “Chip” Stewart advised a state legislature on a draft bill that aimed to limit how political candidates could utilize AI and AI-generated imagery to depict opponents, including in campaign advertisements.

“I looked at [the bill] and thought it was unconstitutional in about eight different ways,” said Stewart, a professor of journalism and assistant provost for research compliance at TCU.

The runup to the 2024 election marked the first major U.S. contest in the era of adept AI, as campaigns deployed the technology to disseminate convincing but fake videos and doctored photos across social media.

In 2023, during his bid to return to the White House, images circulated on X showing Donald Trump hugging Dr. Anthony Fauci, whom the Trump administration had repeatedly discredited. Although apparently AI-generated, the images were blended with real photos showing Trump and Fauci interacting during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This half-fake collage appeared in a campaign video promoting Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ bid for the GOP presidential nomination and was shared without disclaimers.

The DeSantis campaign defended the content as a response to the Trump campaign “continuously posting fake images and talking points to smear the governor.”

Meanwhile, in New York, Blake Gendebien, a Democrat running in the 21st Congressional District against incumbent U.S. Rep. Elise Stefanik, released a parody video featuring AI-generated images of Stefanik singing self-mocking lyrics, with a small-print disclaimer only at the video’s end.

In response, several states passed laws to curb “deepfakes,” machine-created video, audio or images often spread maliciously.

But as Stewart and co-author Jeremy Littau, associate professor of journalism at Lehigh University, note in a study to be published in the upcoming Colorado Technology Law Journal, the First Amendment protects false political speech, posing steep constitutional hurdles for lawmakers.

Since 2019, at least 20 states have passed legislation regulating the use of false audio, videos and photos of candidates in election campaigns. In the Colorado Technology Law Journal study, Stewart reports that no one has been prosecuted to date for failing to label false AI-generated political content.

Courts’ caution reflects a longstanding principle: False claims, AI-generated or not, are often best countered in the “marketplace of ideas” rather than by law, Stewart said. Laws regulating political speech must meet Supreme Court standards, using the “least restrictive means” to address the problem without limiting protected expression.

Consider the case of Xavier Alvarez, a former California water district board member who falsely claimed to have received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

In U.S. v. Alvarez, the 2012 Supreme Court struck down the Stolen Valor Act of 2005 criminalizing lying about military honors, leaving Alvarez’s conviction overturned but the court of public opinion unconvinced.

The ruling reaffirmed counterspeech — challenging, correcting and publicly exposing falsehoods — as the preferred constitutional remedy.

“Let news reporters come out and say, ‘Hey, that guy’s lying.’ And let other people at the meetings say, ‘This guy’s lying.’ He was basically revealed to be a fraud,” Stewart said. “Rather than have the government step in to determine what’s true or false, we let the people sort that out.”

LABELS AND LIES

Stewart’s work underscores that the responsibility to distinguish fact from fiction doesn’t rest solely with judges or journalists — everyone must engage critically with the information they encounter.

Visual content, once a reliable signal of reality, is now muddied by AI-generated images and videos, including celebrity deepfakes. An “AI Tom Hanks,” for instance, promoted miracle cures, stoking confusion over what is real.

“To now have imagery and videos that are not necessarily real, that really creates some cognitive dissonance,” said Alexis Shore Ingber, Stewart’s co-author and an assistant professor of communication at Syracuse University.

In July 2023, seven leading U.S.-based AI companies — Google, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, Anthropic, Inflection and OpenAI — committed to voluntary safeguards including research into bias and discrimination risks and the creation of signifiers such as watermarks to help people identify AI-generated content.

Still, enforcement remains inconsistent. Last October, the Tech Transparency Project reported that 63 of Facebook’s top 300 political or social ad spenders had employed deceptive or fraudulent practices.

“The whole premise of democracy relies on rational people making fact-based decisions,” Stewart said. “Lies have always been there, and they’re always going to be there. The concern is that there are more lies now, and they’re harder to detect.”

In a 2025 study sponsored by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), Stewart and his co-authors, Ingber and Ellie Griffin, a TCU senior majoring in journalism and theatre, examined whether legally mandated warnings on AI-generated content are effective. The team tested if mandatory labels on machine-made content in political campaigns could alert voters to potential unreliability and reduce the circulation of fake media.

“There were state laws that were being enacted that were requiring social media companies to have a label warning against AI,” Ingber said. “But there wasn’t really any sort of evidence detailing if those labels were actually going to be effective.”

The team explored how users recognize AI-generated content on their feeds, comparing community notes — labels added by other users — and legal tags across 12 posts, some labeled, others not. On a real feed, posts might carry badges with accompanying text (“AI info” on Facebook or “Readers added context” on X) flagging AI-generated content.

The trio found users perceive AI-flagged posts as less credible and less shareable than unflagged ones. Participants were likelier to repost AI-generated commercial content than AI-produced political content. The study also concluded that the label source does not matter: Warnings from legal mandates and community notes equally informed users of a post’s inauthenticity.

Labels aside, Stewart is reinforcing the need for individual vigilance: “Part of your duty as a citizen is to be informed,” he said. “But be appropriately skeptical.”

While labels influence perceptions of credibility, the findings suggest that it’s up to everyone to be on the alert for AI-generated content, Ingber said. “We don’t want people to feel like this is someone else’s problem and not theirs.”

GARBAGE IN, GARBAGE OUT

Amid the surge of AI-generated distortions, Jie “Jackie” Zhuang, an associate professor of communication studies at TCU, examines how to help people understand emerging health risks and adopt behaviors that improve outcomes, such as following credible vaccination or disease prevention guidance.

AI plays a central role in health care, powering virtual assistants that analyze patient-reported symptoms and forward daily health reports to physicians. But the technology relies on mathematical models that don’t add up for all. Health care-oriented AI tools predict patient outcomes based on past evidence. “But when we look at the evidence that already exists,” Zhuang said, “there has already been bias in it.”

Nearly 30 years after a supercomputer defeated chess champion Garry Kasparov, AI has become an omnipresent tool and sometimes unruly storyteller. TOONS17 | ISTOCKPHOTO

A 2024 study Zhuang co-authored for Ethnicity & Health found that algorithmic bias in AI health care applications stems largely from unrepresentative data, stereotypes embedded in medical records and insufficient oversight, leading to misdiagnosis and undertreatment of marginalized people. While AI holds potential to improve health care, its proper use requires meticulous monitoring and bias mitigation strategies to ensure equitable outcomes.

Zhuang’s 2025 Digital Health study demonstrated that AI can enhance health care access and outcomes in the Global South through telemedicine and predictive modeling, aiding early disease outbreak detection and guiding use of limited resources.

Progress is hindered by inequitable biotech partnerships. Many AI health startups are concentrated in the U.S., United Kingdom and China, while investment from Western biotech companies in the developing world remains minimal. Regulatory gaps and difficulties integrating data across health care systems further complicate AI implementation in these regions.

A 2024 Revista Bioética study cited in Zhuang’s work showed many low-resource countries still rely on paper-based records, causing fragmented, decentralized data, especially in infectious disease surveillance. Digital exclusion can slow critical public health monitoring, such as tracking vaccination coverage, leaving communities more vulnerable to preventable illnesses.

The Digital Health paper concluded that AI built on Global North datasets must be recalibrated for local contexts to reduce — not deepen — preventable health disparities. A Machine Learning for Health study, for example, piloted an AI fetal monitoring app in rural Guatemala using local data, allowing 39 care providers to assess fetal heart rate and maternal blood pressure for roughly 700 women and minimizing delays in treatment.

“If we want to use AI-based health algorithms to reduce health inequity, we need to make sure that the evidence we provide is equitable,” Zhuang said. “When I was a grad student, that wasn’t an AI era yet. But we were told that with whatever data analysis software we used, it’s really like garbage in, garbage out. I think the same idea applies to AI.”

That concept paints AI as merely a tool. Human programmers are responsible for its training and, therefore, its output and value. “We shouldn’t blame the AI models themselves,” said Wei, the computer science professor. “We need to look at how we train and use them.”

FEMA’S FIRESTORM

Zhuang and former colleague Lindsay Ma, now at the University of Massachusetts Boston, are extending their research into crisis communication, examining how AI-generated misinformation shapes public understanding and response to disasters. Their ongoing Arthur W. Page Center-funded study draws from FEMA’s 2024 public relations crisis following Hurricane Helene.

In the storm’s aftermath, rumors spread that disaster relief was insufficient or diverted to migrants. Social media amplified the misinformation: Amy Kremer of the Republican National Committee reposted an AI-generated image on X of a girl holding a puppy in floodwaters, writing, “This picture has been seared into my mind.” In one version, the girl appeared to have an extra finger — a telltale flaw helping confirm the image’s AI origin. Kremer’s post alone drew 3.1 million views and 1,600 reposts, showing how quickly false narratives could spread and shape public perception.

In reality, FEMA provided more than $135 million in aid to six Southeastern states, supplying meals, water, generators and more than 500,000 tarps. Thousands of North Carolinians were rescued or supported through the agency, and the state received $100 million in transportation funds to repair roads and bridges.

Then-Vice President Kamala Harris and FEMA officials urged residents to apply for aid and warned that misinformation was discouraging people from seeking help. FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell later called the surge of false claims “the worst that I have ever seen,” as major news outlets reported many originated from AI sources.

“FEMA put a lot of misinformation correction on their website. But the public trust for FEMA and even for the government, in general, has been diminished. … That really has a lasting impact.”

Jie “Jackie” Zhuang

“FEMA put a lot of misinformation correction on their website. But the public trust for FEMA and even for the government, in general, has been diminished” by the AI-generated misinformation, Zhuang said. “That really has a lasting impact.”

Zhuang said her research, which examines how people interpret and respond to misinformation after it has been identified as AI-generated, aims to better equip users to respond when they confront false AI-created information.

She emphasized the stakes: “Let’s say in the future, whether it’s a national agency or state agencies sending out a flood warning … do people still trust those agencies? With the challenges we face with AI-generated misinformation, our mission to cultivate critical and analytical thinking has never been more essential.”

THE HUMAN FACTOR

AI is a tool, much like the calculator Zhuang saw on her daughter’s school supply list. AI programs can expedite tasks and expand possibilities, but their value — and potential pitfalls — depend on the user.

“Even until high school, we really didn’t use calculators. We had to master the calculation in our mind or write it out. … You understand how math really works,” she said. “But I understand the school’s side of the argument. If you can use the calculator to do the calculation in two seconds, why would you spend 20 minutes?”

Properly wielded, AI can enhance problem-solving and decision-making; left unchecked, it can mislead or dull critical judgment.

Wei stressed the importance of developing foundational skills before relying on AI, noting it could replace early-career coding jobs but also augment skilled professionals. “If you’re already capable, you’re already very senior, it will make you more powerful,” he said. “But there will be a hit on the junior-level programmers because they can be easily replaced. Here’s the dilemma: senior developers, senior people, in whichever field, used to be junior.”

At its core, AI is software that learns from human-created content — Wikipedia pages, news articles, forums and social media — and predicts what comes next. “That’s like self-supervised learning,” Wei explained. “We let the model figure out the correlation.”

From there, AI tools continually learn through trial and error, helping remove harmful examples, such as biased outputs that assume doctors are male and nurses are female, highlighting the importance of careful oversight.

Wei said his initial motivation for studying AI was to become a better teacher. He wanted to show students how to harness its power without stifling their own capacity to do the learning. That led him to launch a faculty workshop series covering how language models work and how AI can support research, pedagogy and creative projects. The fifth and final workshop addressed ethical considerations, ensuring faculty participants left with a framework for responsible use.

Even as AI accelerates tasks and expands how people generate knowledge, Wei warned that users must mindfully evaluate its outputs. “People trust AI. So, what if we just use AI’s answers to do things and we get into trouble? Who is accountable?”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

AI in Academia

Xiaolu Zhou is working to bring TCU classrooms into the future.

Research + Discovery

AI² CENTER AT TCU

The university has built AI infrastructure the way it once built libraries — as a foundation for the next century of research. The new AI² Center enables TCU to operate this technology securely and ethically from campus.

Research + Discovery

AI on Fashion’s Cutting Edge

Instructor Leslie Browning-Samoni weaves AI into her merchandising curriculum.