Politics 101

Students appraise the political landscape

As a contentious campaign season marched toward Election Day, TCU’s Scharbauer Hall hummed with energy and anticipation, much of which radiated from millennials preparing to cast their first votes in a presidential election.

At the center of campus, political science professors taught classes on topics ranging from the U.S. electorate to the evolving role of the media. The instructors’ expertise, insights and historical perspectives – often the product of decades of research – provided students context for what was an extraordinary presidential election campaign.

EARLY LESSON

An 11-year-old James Riddlesperger lingered around the family dinner table, dissecting and debating the historic 1968 presidential campaign, which saw the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy and an election victory for Richard Nixon. A dozen or more presidential elections later, Riddlesperger, now an expert on the executive branch of government, spent the 2016 election year analyzing the candidates through rigorous academic inquiry.

James Riddlesperger, professor of political science.

“While many observers are caught up in the day-to-day activity of the campaign, social scientists take a broader view because we believe that human behavior can be understood in patterns,” said Riddlesperger, professor of political science, who arrived at TCU in 1982 when the department boasted six professors. Today it has 16.

Throughout the 2016 election cycle, pundits, journalists and academics have emphasized the personalities of political contenders along with gender and age. Riddlesperger and his colleagues added one more variable: the young-adult undergraduates they teach.

“This may not be our first rodeo, but it’s important to remember that our students are new, both to voting and to study of politics at the university level,” Riddlesperger said. “The texts they read and the lectures they listen to are, in many respects, tools to frame discussions that allow [students] to articulate questions, engage in dialogue and give them something to think about.”

Political science classes at TCU are filled to capacity, and the department’s professors watched their students move beyond superficial understanding of political issues and controversies to focus on the rationale behind the headlines.

Eric Cox, associate professor of political science.

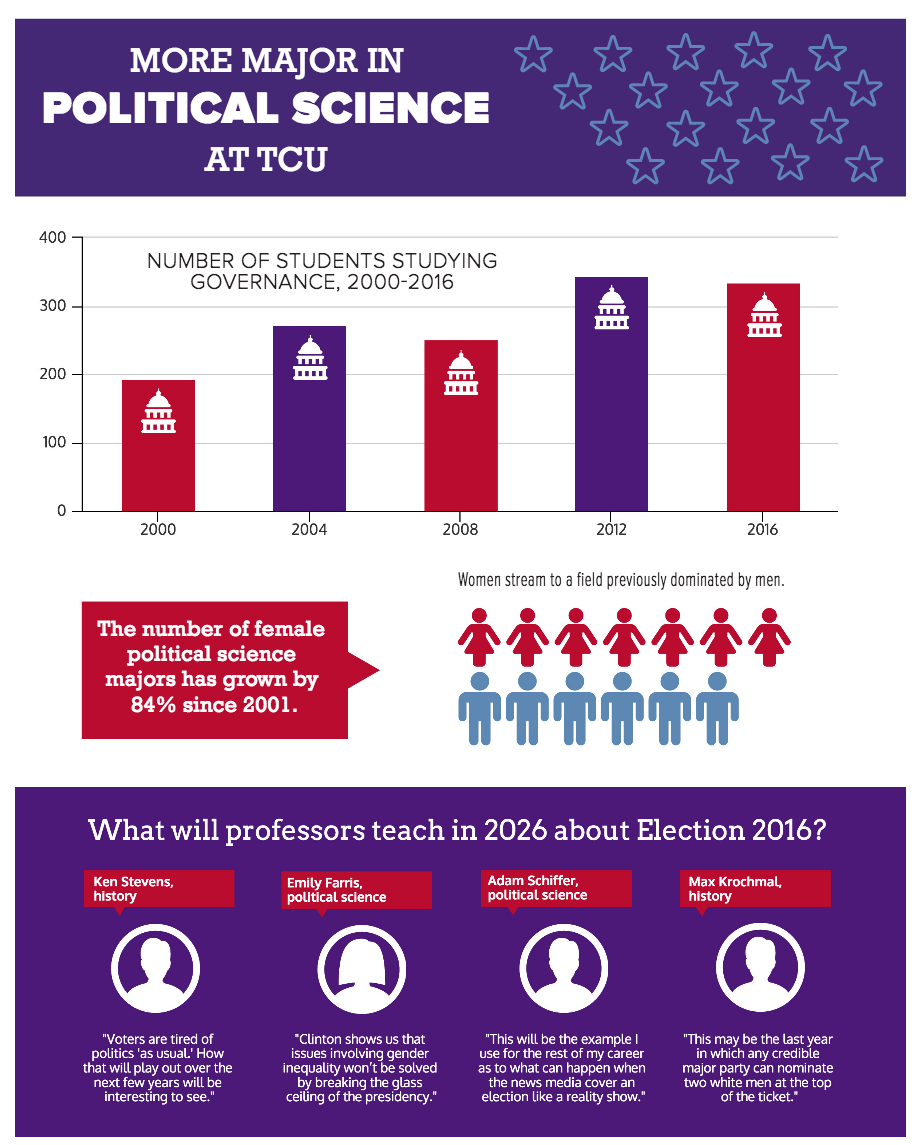

“It’s been really fascinating to listen to the students talk and debate in the class and outside of it,” said Eric Cox, associate professor of political science and chair of the department, who added that about 350 undergraduates have declared a major in political science. “Even as the level of public discourse continues to become more extreme, our students have continued to speak to each other in a civil manner.”

Becca Fitzmaurice, a junior from Denver, appreciated her classmates’ approach to studying the political process during an often divisive campaign season: “A lot of questions run along the lines of ‘how did we get here’” said the political science and criminal justice major. “But if you’re involved in the political science department, you dig in deep with your classes, analyzing data and having good discussions. TCU really is a safe space to talk about this stuff.”

EDUCATED VOTERS

Grant Ferguson, director of political science outreach and public service internships.

And talk the students do – in class, office hours, dining halls and dorms as well as with family members, something Grant Ferguson, director of the department’s outreach and public service internships, considered essential to the academic growth of his students. “What they learn in class will shape their perspective,” he said. “But so does speaking to their older friends and their families, which is all part of a broader education.”

Political science coursework, meanwhile, challenged students to examine the partisan positions and claims with discernment. For instance, during the fall semester, Vanessa Bouché, assistant professor of political science, taught “Topics in Political Methods.” Her students examined why political pollsters around the country had unprecedented difficulty gauging how Americans were expected to vote in November.

Vanessa Bouché, assistant professor of political science.

Jack Dougherty, 21, one of Bouché’s students, found an explanation in the social desirability bias. “That’s when people may not want to give their own honest opinion because it could raise eyebrows,” said the senior from Arizona majoring in political science and economics.

In Bouché’s class, students designed experiments to test the theory underlying the social desirability bias. “If any question is sensitive in nature like social taboos including sexism or racism, then you have to work hard to craft questions that will get accurate responses because people often don’t want to admit their beliefs,” Dougherty said.

In the fall semester’s “Campaigns and Elections” course taught by Joanne Connor Green, professor of political science, students examined the pluses and pitfalls of a so-called permanent campaign, where elected officials focus as much – if not more – on re-election as on governing.

Joanne Connor Green, professor of political science.

“One of the ‘pros’ of a permanent campaign is that the pressures of re-election help keep politicians accountable and in touch with their base,” said Green. In a mid-September class, students proceeded to offer their take on what constituted the cons:

“Elected officials are afraid to be bold or make tough decisions if they’re always in campaign mode.”

“Campaigning is all or nothing while governing requires compromise.”

“They focus too much on raising money.”

Ferguson taught “Campaigns and Elections” during the Spring 2016 semester and focused on voter turnout research, a concept that resonated with Sage Hopkins, a senior from Ohio.

“We learned that one of the most effective ways to get out the vote was for someone to ask you face to face to actually vote,” said the sociology and political science major. “So as an RA last semester, I made a bulletin board with the candidates remaining in the primaries at that point and their bios along with facts about the government and information about how we derive the right to vote. My residents were really into it.”

MUTED ENTHUSIASM

Fitzmaurice said that while “some of my classes have influenced the way I’m going to vote in the future, the information I’ve gained just won’t influence my vote choice in this particular election.” She described the current political campaigns as singular in the extreme: “None of the models fit it. None of the previous information on how candidates structure their campaigns are appropriate; and none of the debate protocols are even being followed,” she said. “It is such a wild thing that what I’ve learned cannot even be applied to this election.”

The 20-year-old Fitzmaurice is not alone in her disappointment. The department’s professors have observed that the negatives associated with the political candidates have translated into ambivalence. Today’s students are far more subdued than in presidential elections remembered for mobilizing American youth, most notably John F. Kennedy’s victory in 1960, Ronald Reagan’s success in 1980 and the landmark election of Barack Obama in 2008.

Adam Schiffer, associate professor of political science.

“It’s not that everybody on campus loved Obama, but the ones who did were very vocal about it,” said Adam Schiffer, associate professor of political science. “During the 2008 [presidential] campaign, you saw tons of T-shirts, backpacks and bumper stickers on cars in the student lots.”

Ferguson observed ambivalence regarding the 2016 presidential candidates in the classroom. “I’ve told [all the students] that in some ways it’s an abnormal election for them to be voting in for the first time, starting with the fact that with no incumbent and no incumbent [vice president] running, the primaries were especially competitive and divisive.”

Allegra Hernandez, a senior political science and art history major, felt electorate frustration all the way in Albania, where she was an intern with the U.S. State Department during the Spring 2016 semester. “Albania is one of the most pro-American countries in the world,” said the 21-year-old from New Mexico. “They see us as this amazing democracy, so they really struggled with some of the rhetoric coming out of the campaigns.”

Returning to campus for the fall semester, Hernandez noticed that “nobody I know is really excited about either (presidential) candidate, which goes along with research that has shown that most of us in my demographic didn’t vote for these people in the primaries.”

SOCIAL MEDIA MATTERS

As befitting their generation, the millennials – those Americans born between 1981 and 1996 – have taken their discourse beyond face-to-face encounters and into the virtual realm. A recent study by the nonprofit Pew Research Center reported that some 61 percent of internet-using millennials rely on Facebook for the majority of their political news.

Students watch the final presidential debate at an on-campus event sponsored by the Student Government Association.

Students such as 20-year-old Cory Hood found it almost impossible to tune out the political chatter on social media channels. “I get news off Facebook and Twitter whether I want to or not,” said the sophomore political science major from Burleson, Texas. “What I usually see are just headlines, so I try to do a little more research.”

When the noise on Facebook became too strident, Hernandez said she hit the mute button. “I block the people who go really negative,” she said. “What they’re posting won’t change my opinions, and I don’t have any desire to see it.”

While Schiffer didn’t think political elections will be won or lost on social media, he nevertheless noted that the immediacy inherent to Snapchat, Twitter and other social media sites that resulted in intensifying political controversies.

“I tell students that their Twitter feed is only as good as the people they follow, meaning they need to focus on intelligent sources,” said Schiffer, who taught “Media and Politics” in the fall semester. “There’s a lot to the social media revolution, but you don’t want to surround yourself with essentially your own opinion at the exclusion of differing ideas.”

Schiffer said social media magnifies voices in two ways: “It gives the worst of the worst a larger platform,” he said. “But then it also gives people on the other side a way to mine their opponent’s social media for the ugliest comments, which they then exploit for their own gain.”

Emily Farris, assistant professor of political science.

Emily Farris, assistant professor of political science, dubbed that social media phenomenon the echo chamber effect: “I love how social media can encourage engagement and elevate a diverse set of voices, but it also plays to the natural tendency for us to retreat and listen mostly to those who share our own opinions.

“Political reporters tend to go to the same sources over and over again, and for presidential elections, those experts are almost always white or men,” Farris said. “As a way of amplifying the voices of experts who aren’t normally heard on Twitter, we’ve been developing hashtags for #womenalsoknowstuff and #POCalsoknowstuff.” (POC stands for “people of color.”)

Green observed another emerging phenomenon: “Social media has some costs, one of which is the idea of how we define activism,” the professor said. “The Vietnam generation marched in protest, petitioned door to door to inform their neighbors about issues and went to city council meetings in order to make their voices heard.

“Such investment in change required resources like time, energy and effort,” Green said. Today, “many equate political activism with signing an online petition or reposting a comment.”

GENDER AND THE GENERATIONAL DIVIDE

When Hillary Clinton accepted the Democratic Party’s nomination in August 2016, she shattered the glass ceiling for female candidates in U.S. national politics. But among TCU students, the politician’s moment in history generated far less buzz than professors and other academics might have anticipated.

“What’s interesting to me is that the millennial generation completely takes for granted that women are equal and that they’ve always had this opportunity,” said Bouché. “We are not doing our students any service to gloss over the fact that this is a historic moment.”

TCU’s Student Government Association sponsored an October 2016 debate watch party. Many of those at the event were eligible to vote for a presidential candidate for the first time.

Hopkins viewed the nomination of a woman for U.S. president as simply a matter of time. “Whether or not it was Hillary Clinton or Carly Fiorina, it didn’t feel like a major moment for me as a woman,” said the 21-year-old whose father helped ignite her passion for politics. “I actually think it is progress when we stop thinking of things like that as a big deal.”

Fitzmaurice, 20, agreed: “Women my age have grown up with Hillary, so this felt a bit inevitable. Plus, she’s played down her feminine qualities so much that it’s almost weird to hear it emphasized that she is the first female presidential candidate from a major party.”

But Riddlesperger said that Clinton’s party nomination probably resonated more for the mothers and grandmothers of the political science students than with most millennials on campus. “For women who were in the civil rights battles during a time when the notion of a woman doing anything other than being supportive of her husband put them on the fringes, Hillary Clinton’s campaign has been truly momentous.”

Feedback from some recent TCU graduates has shaped Green’s belief that current students’ opinions about gender and politics might shift once they start their careers. “Some of my former students in their 20s are now seeing new realities based on their experiences in the workplace,” the professor said. “Those young women, who were raised in a post-feminist environment where their parents told them they could do anything they wanted to, now view gender in a different way than they did while they were in the protected school environment.”

DEMOCRACY IN ACTION

Throughout 2016, transforming ideas into action at the ballot box became a campus-wide effort for some students. The TCU Student Government Organization’s Votermobile – a golf cart decked out in flags and red, white and blue streamers – cruised campus with student leaders distributing voter registration forms and absentee ballot requests for all 50 states.

James Riddlesperger and his students discuss ways to balance differing ideologies in making U.S. public policy in his “The Politics of Freedom and Order” class.

“We definitely want our students to exercise their right to vote,” said Green, who added that some students visited during office hours for help navigating the registration process, which can vary significantly from state to state. “But as we’re helping them get their absentee ballots, we do hear a lot of ‘Why should I vote?’ or ‘My vote doesn’t matter.’”

“The truth of the matter is there’s almost a sense of dread about voting,” said Hernandez, who plans to graduate in May. “We know it’s our obligation and civic duty, but no one is really excited about it, even though for most of us it’s our first time.”

For people despairing about the fate of the nation after Jan. 20, 2017, when the president-elect takes the oath to lead the nation for four years, Riddlesperger offered a seasoned political historian’s perspective: “If the United States can survive Warren Harding as president,” whose early 1920s presidential legacy includes the Teapot Dome and other political scandals, “then we will survive the 45th president, too.”

Infographic by Dick Jones Communications. Sources: TCU Registrar’s Office and Dick Jones Communications.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

PolitiFrog Jumps into the Election Fray

Students ’splain the campaigns and candidates.

Campus News: Alma Matters

Rocking the Vote

Emily Farris studies social capital and why black women participate more in politics.