The Native American and Indigenous Peoples Initiative at TCU recognizes the history of the land and strengthens ties with Native communities. Illustration by Sam Ward

A New Story on Ancient Land

TCU’s Native American and Indigenous Peoples Initiative builds curiosity, knowledge and relationships.

On an unseasonably cold and rainy day in October 2018, about 100 people gathered inside a campus auditorium. The dedication of TCU’s Native American Monument was supposed to be held at the granite marker itself, placed near a heritage oak tree between two buildings constructed in 1911. But the weather had driven the group inside.

The crowd included TCU community members and leaders from the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, whose ancestral land the TCU campus now occupies. The Wichita nation had brought traditional drums for the occasion, and university officials presented the delegation with blankets and tobacco grown by a Native student’s family.

J. Albert Nungaray served on the committee that developed TCU’s Native American Monument. Dedicated in 2018, the monument acknowledges the Native people who have lived on the land where TCU now stands.

J. Albert Nungaray ’17 rose to speak. As he surveyed the crowd, he still couldn’t believe he was a key part of the effort to honor Native American heritage at his alma mater. Nungaray, who is of Tewa and Wixarika descent, grew up in poverty in El Paso. Many of his peers did not finish high school, much less college.

After working for a few years, Nungaray had completed community college and transferred to TCU. He didn’t meet a single other Native person during his first two semesters at TCU. But in his second year, he became friends with a fellow anthropology student who was a citizen of the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana. The two formed a Native and Indigenous student association, reviving an effort started more than a decade earlier by students including Tabitha Tan ’99.

Nungaray later served on the committee that developed the monument and its text, which respectfully acknowledges all Native people who have lived on the land.

Standing in front of the group assembled for the dedication, he felt like he had finally accomplished something with his life. “I felt like I’d actually done something to make myself, my people and my family proud of me,” he said later. “That monument is for everybody. Those words are for everybody. And they’re words that are going to live on long after I’m gone.”

The monument is a visible reminder of TCU’s Native American and Indigenous Peoples Initiative, which seeks to build relationships with Native communities, help non-Native students learn about Indigenous culture and transform TCU into a welcoming space for Native students, faculty and staff.

Launched in 2015 as a grassroots effort, the initiative has become a university priority. An annual symposium and numerous guest speakers teach students about issues important to Native nations, such as tribal sovereignty and the disproportionate rates of violence against Native women and girls. Recently hired Native faculty have created courses in Native history, literature and culture.

The university’s land acknowledgment, which recognizes that the campus is built on land taken from the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, is read at convocation and commencement and posted in all residence halls. Students have attended and volunteered at powwows and learned from members of the local Native community.

Area museums, churches and schools have looked to TCU for guidance as they embark on their own programs to build bridges with the Native community. Still, people active in the projects said that these accomplishments should be seen as just the start of a larger journey.

“TCU has been careful and thoughtful in its work with Native communities,” said Wendi Sierra, associate professor of game studies in the John V. Roach Honors College and an enrolled member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, Turtle Clan. “It has always been done in a spirit of reciprocity and a spirit of open desire to understand and to collaborate. We’re building slowly — but we’re building thoughtfully, and that’s the right way.”

“That monument is for everybody,” said J. Albert Nungaray, an alumnus of Tewa and Wixarika descent. “They’re words that are going to live on long after I’m gone.”

Local, Living History

TCU’s outreach to the Native community began with Scott Langston, a now-retired instructor of religion who is also a scholar of history. Sensing that his education had omitted Native American perspectives, Langston, who is white, in the early 2000s started reading works by Native authors, attending events and volunteering with the Native community.

In 2015, he drove to Oklahoma City to visit with Chebon Kernell, a citizen of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, a Muscogee/Creek ceremonial leader and an ordained minister in the United Methodist Church. Langston invited Kernell to speak to his religion class about the perspectives of Native American Christians and healing relationships with Indigenous peoples, offering him an honorarium and reimbursement for his travel costs.

The classroom was packed with students from multiple classes, including those of Theresa Gaul, professor of English, who has taught courses in Native American literature.

Energized by the event, Gaul, Langston and Kernell began to plan TCU’s first Native American and Indigenous Peoples Day Symposium, which occurred in October 2016. That day’s events drew 1,000 participants, including numerous members of the Dallas-Fort Worth Native community.

Gaul, also director of TCU’s core curriculum, said meeting those neighbors was rewarding. “Too often in academe, we can live in an abstract, intellectual world of questions and issues and problems,” she said. “Doing work with living people has been really transformative and has helped to shift a lot of my teaching and research to the idea of the local and to take up topics that are connected to where I reside in Texas.”

The symposium is one of TCU’s efforts to improve what Kernell called the “Native American literacy rate” on campus. When they arrive at TCU, most students know very little about Native culture or issues, leaders of the initiative said. What information they did learn in school is typically about the past; it’s not uncommon for students to assume Native people are extinct. Few are aware that the 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States today are sovereign nations with their own governments and, in many cases, thriving businesses on and off reservations. Nearly 40 of those nations, including the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, are headquartered in Oklahoma.

“TCU has been careful and thoughtful in its work with Native communities. It has always been done in a spirit of reciprocity and a spirit of open desire to understand and to collaborate.”

Wendi Sierra

Texas is the site of reservations for three federally recognized tribes: the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas in the Big Thicket region; the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas outside Eagle Pass; and the Tigua people of Ysleta del Sur Pueblo near El Paso. But Native people — members of tribes that are federally recognized, state-recognized or neither — live throughout the state. The Dallas-Fort Worth area is home to well over 100,000 Native people, partly a result of a U.S. government policy adopted in the mid-1950s that encouraged Native people to relocate from rural reservations to cities, including Dallas.

TCU students have embraced the chance to learn what they didn’t in secondary school, said Kernell, who has spoken at numerous symposia and panels. “At all of those events, I have witnessed a hunger,” he said. “I have witnessed a sense of genuineness. I have witnessed honesty that students wanted to know more, and they were intrigued by what they were hearing.”

The Legacy of Village Creek

In recent years, the TCU community has learned about the history of the land where the campus sits today. Until the mid-1830s, the Wichita, Waco, Tawakoni and Keechi, collectively known as the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, lived in a vast area stretching from modern-day Kansas to Central Texas. But in 1838, the Republic of Texas’ second president, Mirabeau Lamar, declared an “exterminating war” against Native people in Texas that would end in their “total extinction or total expulsion.”

One of the battles occurred at Village Creek, near the eastern edge of today’s Fort Worth. On May 24, 1841, Gen. Edward Tarrant led a deadly attack on settlements of Wichita and other Native people that drove them permanently from the area. White settlers moved in and took the land. The state of Texas briefly established reservations for the tribes in the 1850s, but by the end of the decade, the state and U.S. governments had removed them to today’s Oklahoma.

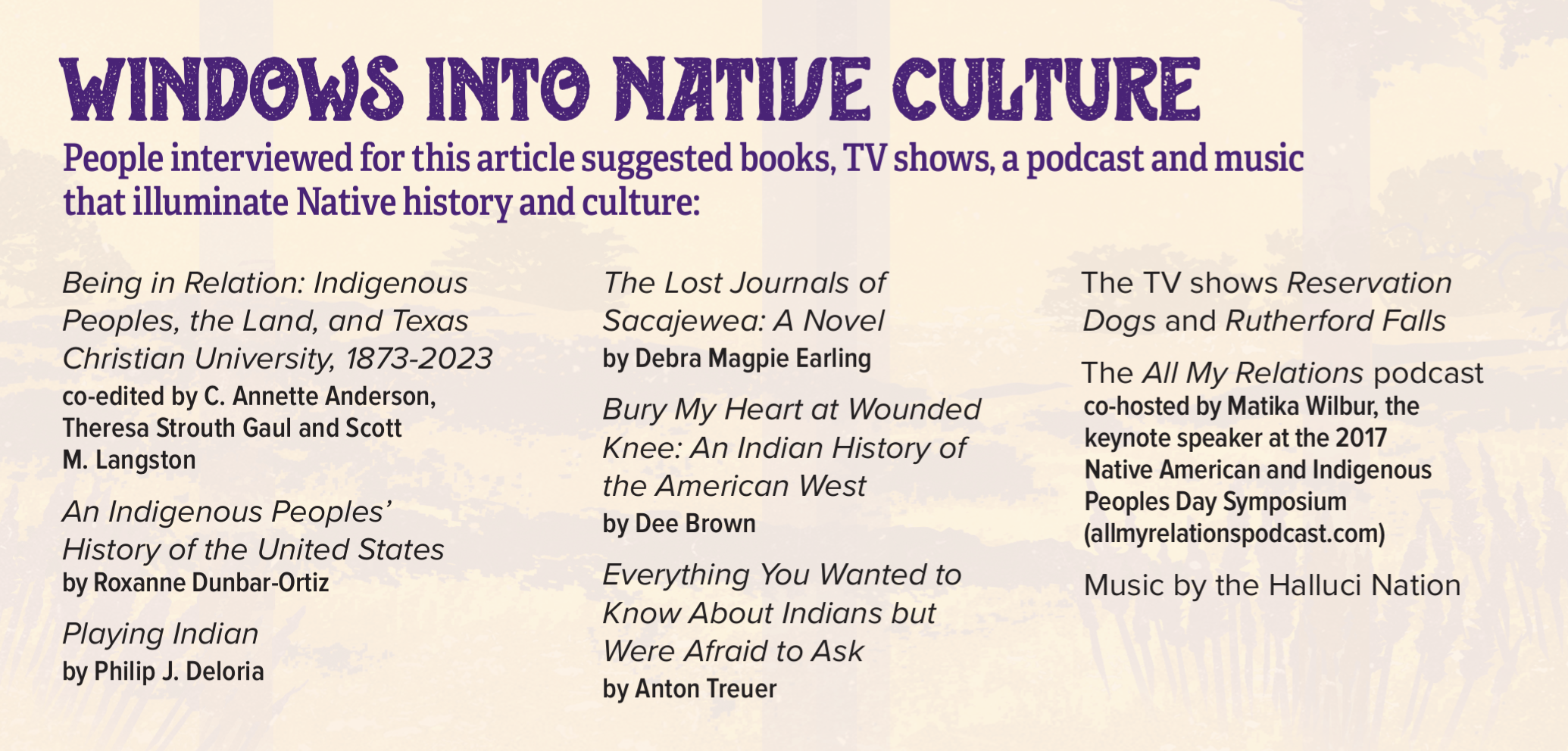

Addison and Randolph Clark’s access to all three sites that TCU has occupied — Thorp Spring, Waco and Fort Worth — was possible only because the Native people who lived there were driven out, Langston writes in an essay included in Being in Relation: Indigenous Peoples, the Land, and Texas Christian University, 1873-2023, published in May by TCU Press.

Today’s Native American Monument was created to acknowledge that history. In 2016, TCU asked leaders in the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes for permission to place the monument and invited them to participate in the design process. The nation today counts just fewer than 4,000 citizens but many more descendants and is headquartered in Anadarko, Oklahoma. The fact that TCU reached out to the nation, said Wichita and Affiliated Tribes President Amber Silverhorn-Wolfe, showed the university was being intentional about recognizing the wrongs of the past.

“If we could go back in time, obviously we wouldn’t want someone taking our homeland and building upon it, and then profiting and not even teaching about us,” she said. “But coming from a positive standpoint, I’m thankful TCU has even thought to have these conversations, and I hope the faculty and administration continue to allow a space for them.”

The monument features the phrase “This ancient land, for all our relations” in both English and Wichita. An additional inscription reads, “We respectfully acknowledge all Native American peoples who have lived on this land since time immemorial. TCU especially acknowledges and pays respect to the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes upon whose historical homeland our university is located.”

Through continued collaboration with the Wichita tribal nation, TCU’s Native American Advisory Circle, which includes faculty, staff and students as well as local Native leaders, drafted a land acknowledgment that was adopted by the university in 2021. The statement incorporates the monument’s language as well as the sentence, “TCU acknowledges the many benefits, responsibilities, and relationships of being in this place, which we share with all living beings.”

TCU’s acknowledgment is a model for other entities because the university collaborated with the Wichita tribal nation, said Annette Anderson, a member of the advisory circle and a descendant of Chickasaw and Cherokee people. “TCU came up with one of the best examples of a land acknowledgment; it was driven by the Native people,” she said.

“They met with Native community representatives to write it, and it was not driven by the administration. They really wrote a true story in their land acknowledgment.”

These Things Still Matter

Wendi Sierra, an enrolled member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, Turtle Clan, taught a course on Native pop culture in spring 2024. “It brought the students a different understanding of Native culture than they had gotten before,” she said.

Hours before daybreak on Oct. 7, the day of the 2024 Native American and Indigenous Peoples Day Symposium, Carl Kurtz ’14 set up his lodge, or tipi, on the grass of the Campus Commons. As the sun rose and students headed to class, some stopped to stare at the 25-foot-tall structure adorned with artwork by Kurtz’s daughter.

Throughout the day, Kurtz, who is Potawatomi, welcomed half a dozen classes to step inside the lodge, which his family uses for ceremonies. He greeted the students in Potawatomi, showed them some of his regalia and opened the floor for questions.

Since the first symposium in 2016, Kurtz has used his lodge as a springboard for conversations about issues affecting Native people. He tells the students that he’s not fluent in Potawatomi because his parents were forbidden from speaking it in their youth and that many Native nations are trying to reclaim their languages.

He encourages his listeners to be thoughtful in their speech: Don’t use the term powwow for a meeting or “going on the warpath” to describe an upset state. He explains why he objects to the use of Indians or Braves as mascots: The words trivialize the identity of an entire group of people.

Kurtz urges his audience to talk about these subjects with their Native classmates and professors and to register for courses about Native topics. To Kurtz, the conversation is part of living out TCU’s mission to educate individuals to think and act as ethical leaders and responsible citizens in the global community. “That’s the purpose of being out there,” he said. “To get them to think … to show them it’s not past tense and that these things still matter.”

TCU students now have more opportunities to take courses incorporating Native content and perspectives. Sierra, who also serves as TCU’s Native American nations and communities liaison, taught a course on Native pop culture in spring 2024. The class was one of her favorites, she said, because it offered a contrast to most people’s limited knowledge of Native communities, which focuses on trauma. Sierra did cover that history in her course, but she said her primary aim was to reveal the resilience and strength of Native culture.

Her students listened to music by Native artists and watched an episode of the Marvel animated series What If…? that features a Mohawk character. Their final project was editing Wikipedia articles on Native actors, musicians and game designers. “It brought the students a different understanding of Native culture than they had gotten before, a contemporary understanding, one that was uplifting and celebratory,” Sierra said. “Then we actually did some good in the world, because we added information to the Wikipedia pages of these people who have earned it and deserve it.”

In fall 2023, Gaul invited one of her graduate classes to write the text for a self-guided campus tour that she described as “a re-seeing of campus features from an Indigenous perspective.”

Since the first Native American and Indigenous Peoples Day Symposium in 2016, Carl Kurtz has used his lodge as a springboard for conversations about issues affecting Native people.

The students, who, like Gaul, are not Native, collaborated with Native advisers, including Anderson, to identify and describe tour stops. These included the monument and the Native American Nations Flags Project displayed in the Mary Couts Burnett Library, as well as natural features such as an old oak tree, the pollinator garden and the statue of the horned frog, which in Diné, or Navajo, culture is called grandfather and considered to have spiritual power that can offer protection and blessing.

“Our culture desperately needs allies,” said Anderson, adding that the Native people in Dallas-Fort Worth who are comfortable leading programs are always stretched thin by Indigenous Peoples Day and Native American Heritage Month. “It’s not like we want people to talk for us, but we want people to share what they’ve learned from us with others.”

Appropriate, Not Appropriating

On a Saturday morning in April 2024, Audrey Turco, a senior political science and youth advocacy and educational studies major, stood in the doorway of a gymnasium on the University of Texas at Arlington campus, bathed in the hot-oil smell of fry bread. She and a friend were taking Sierra’s pop culture course, which required them to attend a powwow.

Although Anderson had given the class a primer on powwow etiquette, Turco still felt out of her element. As she stepped inside the gym, she was acutely aware that she and her friend were the only white people in the room. Even though attending the event was obligatory for her class, she worried that doing so was tantamount to appropriating someone else’s culture.

As the women browsed the vendors’ tables, a man smiled and offered to show them around. His warm welcome dissolved the edge of Turco’s anxiety. Later, when the drums began and dancers entered the circle in a slow, rhythmic shuffle, she settled into her seat and studied the participants’ regalia. Turco and her friend ended up staying at the powwow for close to three hours, much longer than they’d planned.

As long as she was respectful, Turco said, she could attend the powwow and share her experience with other non-Native people without overstepping. “It’s OK to seek interest and engage with another culture that’s different from your own in a way that’s appropriate and not appropriating it.”

TCU is working in other ways to deliver on the promises in its land acknowledgment. It has established the Four Directions Scholars Program, which awards a full scholarship annually to two students who are citizens of a federally recognized tribe.

The university is still “a low-literacy environment” with regard to Native topics, Sierra said. “But it’s changing as we do this work, and even as Native issues get more national visibility.” She points to the success of the television series Reservation Dogs, the film Killers of the Flower Moon and the Marvel comic and television series Echo, which stars a Native character. “As we see things change in that pop cultural landscape, and as we have more activities and offerings on campus, I think that we start to develop that literacy.”

TCU’s Native American and Indigenous Peoples Initiative invites all students to ask questions and learn, recognizing they may not have been exposed to Native cultures or values before, she said.

“For non-Native students, it’s an opportunity to recognize other perspectives, other people, and maybe to think critically about their own perspectives,” she said. “When you learn about another culture, you learn a lot about yourself.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Bringing Native American Voices to Campus

Organizer Scott Langston said upcoming panels are a matter of cultural and environmental awareness.

Research + Discovery

Are DNA Ancestry Tests Harmful?

Debunked science resurfaces when consumers misunderstand results.

Research + Discovery

Ancient Manuscript Describes Assimilation of Aztecs

Art historian Lori Boornazian Diel decodes the story of Spanish invasion and the struggle to find a new identity after defeat.