Ann Marie Herbst’s Matchmaking Mission

Now in remission from leukemia, the alumna aims to raise awareness for the bone marrow donor registry.

Ann Marie Vest Herbst ’07 struggled to maintain her pace on the new elliptical machine in TCU’s University Recreation Center. The Spring 2015 semester had just started, and the center wasn’t crowded that Thursday night. Herbst, a contract negotiator for Lockheed Martin, had an alumni membership and exercised regularly. Still, she was out of breath; maybe, she thought, this machine was particularly challenging.

As Herbst pushed herself to finish her workout, she thought about the blood work she had done that day at her OB-GYN’s office. Her daughter, Hayden, was 15 months old, and Herbst and her husband, Jay, hoped to have a second child. She had woken up with night sweats recently and wondered if she was pregnant.

The next day Herbst was home with Hayden when the phone rang. Her doctor was calling with the results of her blood work. The routine tests detected blood cancer.

The rest of that Friday was a blur for Herbst. She called her husband and her parents, Susan LaRoche Vest ’76 and Steve Vest ’76, who lived in Fort Worth. During the weekend, the family, including Herbst’s aunt, Elizabeth “Libby” LaRoche Bowles ’81, gathered to cope with the medical news. Her brother, James Hunter Vest ’05, drove up from Austin. Still, Herbst thought, maybe the blood tests were wrong. Maybe her tests had been mixed up with someone else’s results.

On that Monday, after a bone marrow biopsy, Herbst had confirmation. She had acute myeloid leukemia, or AML, a cancer of the bone marrow that is diagnosed in 21,000 new patients in the U.S. each year and causes about half that number of deaths.

About 70 percent of patients who do not have a family-member match rely on a volunteer donor from Be The Match, a nonprofit operated by the National Marrow Donor Program.

In a healthy person, bone marrow produces blood: red blood cells that carry oxygen, white blood cells that fight infection and platelets that clot the blood. But AML prevents the bone marrow from performing that vital function.

The average age of a person diagnosed with this form of leukemia is 67. Herbst was 29. Her fatigue at the recreation center and her recent night sweats were the only symptoms.

On Tuesday morning, Herbst had an appointment with Dr. Robert Collins Jr., a hematologist/oncologist at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Collins confirmed the diagnosis and sent Herbst to the hospital to start chemotherapy.

Jay and Ann Marie Herbst at UT Southwestern Medical Center. Photo by Leo Wesson

The most difficult aspect of the cancer treatment for Herbst was not being able to see her young daughter. Visitation on her hospital floor was restricted to protect the bone marrow transplant patients, whose immune systems were highly compromised.

Herbst went through four rounds of chemotherapy. Each one kept her in the hospital for at least 20 days. In an effort to stay active, she and her husband walked countless laps through the hallway surrounding the nurses station. Her hospital room filled with pictures of Hayden and gifts from loved ones: her extended family, her sorority sisters, friends she made during her undergraduate semester abroad in Seville, Spain, her colleagues at Lockheed Martin.

Herbst completed treatment in May 2015 and went back to work that July. But in October 2016, routine blood tests showed the leukemia was back. Herbst knew that the typical course of treatment for a relapse was chemotherapy to get the patient into remission, followed by a bone marrow transplant.

Thirty percent of transplant candidates have a family member who can serve as a donor, but Herbst’s brother wasn’t a match. In the absence of a matching related donor, leukemia patients turn to Be The Match, the national registry of people willing to donate bone marrow to a stranger.

Herbst knew that she had a 75 percent chance of finding a perfect match in a donor registry disproportionately filled with other Caucasians. A friend whom Herbst met during her cancer treatments had received a transplant from one of 75 potential matches.

When Collins, who is also a blood and marrow transplant specialist, told Herbst that his search on the national registry on her behalf did not produce a perfect match, she was speechless. “It never even crossed my mind that I would not have a match,” Herbst said. “I just fell apart.”

A Rare Case

For a leukemia patient, the goal of a transplant is to replace diseased bone marrow cells with healthy ones that can form blood again. The blood-forming cells in the marrow are adult stem cells, which replicate themselves to replenish the body’s cells. (“These are completely different from embryonic stem cells, and there are no ethical concerns related to them,” Collins said.)

Transplant patients obtain healthy blood stem cells from donors in one of two ways. In about a quarter of transplants, marrow is taken from the donor’s pelvic bone while the donor is under full anesthesia. But a more common option is a process called peripheral blood stem cell collection, in which the cells are collected from the bloodstream rather than the marrow, and the donor is awake.

Peripheral collection donors are given injections of a medication called filgrastim to move the cells from the bone marrow into the bloodstream (a “peripheral” location). On donation day, blood is drawn from the donor’s arm and passes through an apheresis machine, which separates out the blood stem cells and lymphocytes, a type of immune cell.

Those cells are collected in a bag, and the red blood cells, platelets and plasma are returned to the donor through an intravenous tube in the other arm. Once collected, the healthy stem cells are administered to the transplant patient through an intravenous tube.

For the transplant to succeed, the donor and patient need to have closely matching human leukocyte antigen, or HLA, types. Leukocyte antigens are proteins on the surface of cells that identify which cells belong in the body and which do not. If a donor and recipient do not have compatible HLA types, the donor’s cells will attack the patient’s after the transplant.

HLA types are inherited, and a patient’s best match comes from someone with the same ethnic background. Herbst’s ancestry is 97.7 percent northwestern European, and 57 percent of registered donors are, like Herbst, Caucasian. Herbst’s HLA type, however, is highly unusual, defying the registry’s odds.

And those odds are significantly lower for people of color. For instance, African-American patients have only a 20 percent chance of finding a perfect match through the registry. Migration within and outside Africa, the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and intermarriages have given African-Americans greater genetic diversity than other ethnic groups.

“It never even crossed my mind that I would not have a match. I just fell apart.”

Ann Marie Herbst

Because of the complexity of their ancestry, it is more difficult for African-American patients to find a donor match even among other African-Americans. In addition, only 5 percent of registered donors are black.

Multiracial patients are even less likely to find a match because the specific combination of antigens inherited from their parents is so distinct.

Ann Marie and Jay Herbst don protective masks while waiting for her name to be called for her blood draw. Photo by Leo Wesson

In contrast, the donor’s and patient’s blood types do not have to match. Because the donor’s cells take over the production of blood, the patient takes on the donor’s blood type.

In preparation for the transplant, the patient is given chemotherapy to kill the cancer cells and wipe out her own immune system, so that her body will accept the donor’s cells rather than attacking them.

In a successful transplant, the donor’s cells go to the bone marrow and begin making new bone marrow and blood cells and a new immune system. That immune system can fight any residual leukemia cells.

About 70 percent of patients who do not have a family-member match rely on a volunteer donor from Be The Match, a nonprofit operated by the National Marrow Donor Program. The U.S. registry has 16 million potential donors and coordinates with international registries, including the Germany-based DKMS, or Delete Blood Cancer, to increase that number to 29 million.

But Herbst didn’t have a perfect donor match among any of the international registries.

Weighing the Options

A nurse collects samples of Herbst’s blood. Photo by Leo Wesson

While a transplant using a partially matched donor might successfully treat Herbst’s leukemia, it would also be risky. Herbst’s body had developed antibodies that would react with HLA antigens. The phenomenon, called alloimmunization, had already made it difficult for her to respond to platelet transfusions. Collins knew that chemotherapy alone often was successful in treating Herbst’s particular type of leukemia, and, in Herbst’s case, with less risk than a partially matched transplant.

So Herbst embarked on four more rounds of chemotherapy. She went back to the hospital in Dallas, back to her walking path around the nurses station. Her hair fell out again, faster this time. Hayden at 3 was old enough to miss her mother. Herbst used apps such as FaceTime to chat with her daughter from the hospital room.

In March 2017, Herbst completed her last round of chemotherapy. Collins, a professor of internal medicine at UT Southwestern, said the additional treatment is often successful on its own, but he encouraged Herbst to take an extra step to be prepared in the event of a relapse.

Herbst had filgrastim injections and had her leukemia-free blood stem cells collected in the same procedure that a peripheral blood stem cell collection donor would undergo. This process, called an autologous donation, makes Herbst’s own cells available for a transplant if she relapses and still doesn’t have a donor match.

Nowadays Herbst is in remission. She has returned to work and maintains her normal routine. Although she is cancer-free, having a matching donor would bring peace of mind. However, Herbst’s mission now is to get as many people as possible to join the bone marrow donor registry — and not just to help herself.

“Telling my story is always a little tricky, because we don’t know if I need a transplant to be cured,” Herbst said. “Hopefully this chemo cured me, but it would be silly for me not to try to find a match in case it comes back.

“More importantly, if we can encourage other people to sign up, they could be a match for someone else and potentially save their life.”

Commitment to Hope

While the bone marrow donation process comes with side effects, its reputation of being severely painful is unearned, said Rebecca Garber, a spokeswoman for Be The Match.

At UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Herbst consults with hematologist/oncologist Dr. Robert Collins Jr. and a physician assistant before her scheduled blood draw. Photo by Leo Wesson

That reputation might be because people are unfamiliar with the donation process, particularly peripheral blood stem cell collection, or because television shows and movies have portrayed the process inaccurately. (Garber cited the 2008 movie Seven Pounds, in which the protagonist donates bone marrow without anesthesia.)

Donors experience aches and fatigue, but those side effects are short-lived, Garber said. Most peripheral collection donors recover within a week. Marrow donations come with a small risk of complications connected with anesthesia, but most people recover within a few weeks.

“The message I like to share is that you may be uncomfortable for a couple days,” Garber said. “But the patient has been dealing with this for a year and is super uncomfortable, and you can literally save their life with your eight-hour procedure.”

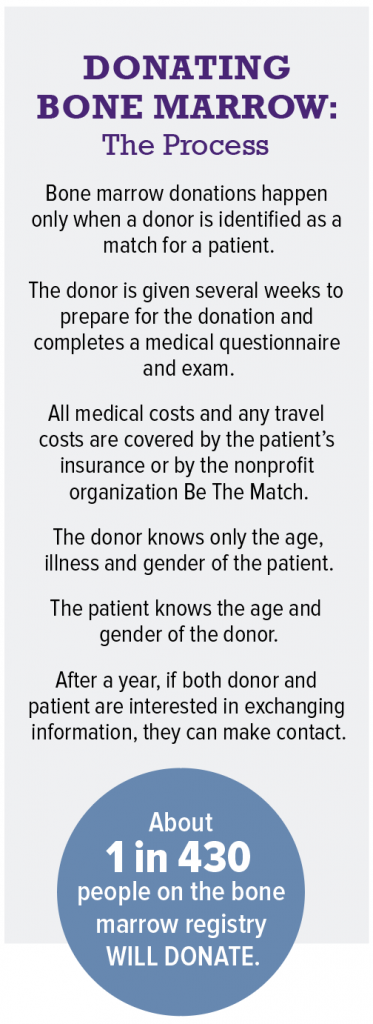

Only half of registered donors who are identified as a potential match for patients go through with the procedure when they are called.

Garber said Be The Match always needs more volunteer registrants, but people who register need to understand the commitment they are making. Only half of registered donors who are identified as a potential match for patients go through with the procedure when they are called.

Of those who do not complete the process, some are unable to donate because of a medical condition. Some are unreachable because they have not updated their contact information, and some are no longer interested in being a donor.

“Maybe they joined in college and they didn’t really know what they were signing up for,” Garber said. “Five years later, when they get the call, they say, ‘Oh, I don’t remember doing that. I’m not interested,’ and they hang up.

“That’s a problem, because a patient could have only one or two matches, and if those people get called and say, ‘I’m not interested,’ then that patient completely loses hope.”

Educating people about the importance of the registry is Herbst’s way of maintaining hope and finding meaning in the trauma of the past three years.

“You have to assign a purpose when you go through something so painful, and I just want to help someone else,” she said. “If I don’t find a match, fine. But to hear that, because of me, someone saved a life — maybe somehow that makes it worth it.”

Join the Registry

Until Dec. 31, prospective donors ages 18-44, whose bone marrow provides the most successful transplants, can join the registry for free at join.bethematch.org/gofrogs

Donors ages 45-60 also can register with a $100 donation to cover the cost of testing their kit for HLA types. Registrants will be mailed a kit containing four mouth swabs used for the testing.

Other Ways to Give

Financial contributions to Be The Match help cover the cost of medical and travel expenses for volunteer donors.

Expecting parents can plan to donate cord blood, which is collected from the umbilical cord and placenta when a baby is born. Cord blood is used in some transplants.

The fourth annual Fight Like Hell Golf JAM is scheduled for April 20, 2018, at Waterchase Golf Club in Fort Worth. Friends of Jay and Ann Marie Herbst started the golf tournament to help the couple with medical bills, and now the Herbsts continue the tradition to raise money for cancer research. In 2017, the event raised nearly $40,000 for the Beat AML campaign, a research effort that is testing treatments targeted at the specific genetic mutations that cause leukemia. Contributions, which are received by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, are tax-deductible.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Alumni

Saving Premature Babies

A doctor’s invention saves babies in the developing world.

Features

KinderFrogs Overcome Developmental Delays

Preschoolers with Down syndrome prep for traditional classrooms.

Alumni

United Front

Connected through social media, two alums bring awareness to spinal muscular atrophy.