How to teach the birds & the bees

Martha Roper is considered one of the nation’s foremost teachers of sex education.

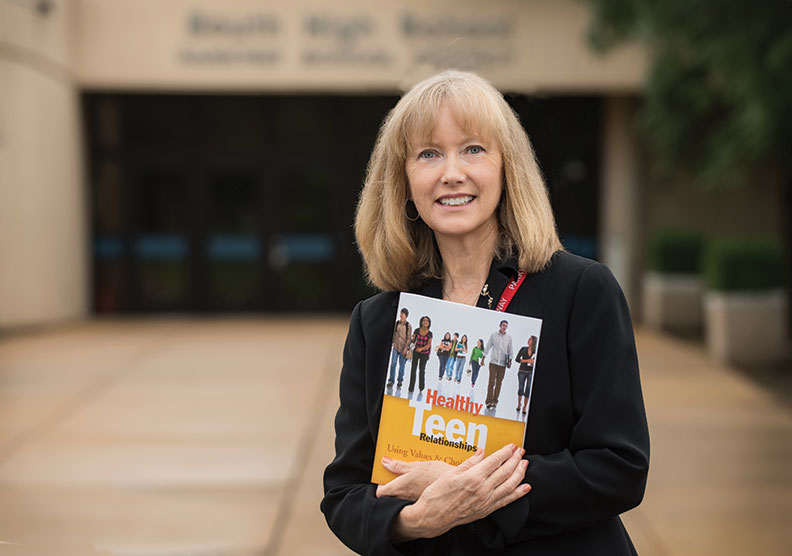

Martha Roper '70 is author of a capstone book for teachers, Healthy Teen Relationships: Using Values & Choices to Teach Sex Education (Search Institute Press, 2011). (Photo by Glen E. Ellman)

How to teach the birds & the bees

Martha Roper is considered one of the nation’s foremost teachers of sex education.

Society changed so much during the 1960s when I went to TCU that upon graduation and moving to the East Coast for work and graduate school, I went into culture shock. I learned to keep up with the local, national and global news to make sure that I had more perspective than campus life offered back then.

While I’m grateful for the cozy experience of TCU, the options for women were limited after graduation. Things really changed after 1970 in terms of getting degrees in previously male-dominated fields, but we know that even now with so much progress, the national conversation continues about “women” professionals.

I learned to find mentors. I noticed years after graduation that successful men had mentors. How one finds help along the way is personal, but clearly, people need guidance and support. Although I never felt the tap on the shoulder that others might have experienced, I did find that help came when I asked for it. Dr. Ron Flowers, my religion professor at TCU, had a profound effect on my thinking, even though I never had a personal conversation with him until many years later. I also developed mentor relationships with several of my former students. Since my field was health education, most of my mentees have become doctors or health professionals.

Growing up in a small town in the 1950s and ’60s, there was no sex education except a 16mm film about fallopian tubes (for girls) and testes (for boys). I had so many questions about relationships and “sex” that went unanswered. I learned about sex in the fifth grade during Girl Scouts. In seventh grade, the physical education teacher handed out three-by-five index cards and invited us to ask her questions. Most of the questions were not related to sex. Yet we were changing clothes in the locker room, and some girls had bras and some didn’t. There were a lot of questions that weren’t asked. Nothing happened at church and home unless there was a problem.

I learned to keep looking for a good fit between my employer and me. Once inside, I learned how to move carefully to teach what kids need to know.

I certainly didn’t know there was a subspecialty in teaching called sex education.After getting a master’s degree in teaching about sexuality at Columbia University in New York, I moved back to Missouri and asked what it would take to get certified and teach in the public schools. I was told: “We don’t need that [subject matter] out here.” Yet, I found a position in a suburb of St. Louis — University City — where sex education had been taught since the 1930s. My specialty was no surprise to them, and when I left that district to move to a higher-paying suburb, the school board gave me a plaque that thanked me for bringing “credit, not controversy” to the system.

What do kids need to know about sex? How does a person find medically accurate information? How do you talk about sex? What is “sex,” anyway? What if you don’t look or feel “normal?” I learned to answer those questions and teach other teachers how to implement programs that work. Because more school districts took the risk to teach about sex after AIDS became so frightening, the research about sex education became clear: Giving accurate and age-appropriate information in public schools works to prevent pregnancy and infections.

Sex education changed from the messages of the past. It went from “Have sex, and you’ll get pregnant” to “Have sex, and you’ll lose your reputation” or “Have sex, and you’ll die.” Sex education is more about learning to communicate and manage conflicts that occur in relationships. Yes, it’s about giving information and telling kids where to find information, but it’s more about learning to be more comfortable with the topic and knowing what to say when you start talking. The need to talk about this personal topic in a sensitive way has become important to our national conversations, as well as our personal ones.

I was featured on “CBS Sunday Morning” in 1982 and received my first death threat; it came in the mail. After being interviewed by ABC national news, there were more threats. I learned to find out who wrote the letters and whether I was in danger. I called the FBI twice to help me sort out the people who wrote such letters.

There has been a dramatic drop in teen-age pregnancy and births in the last 30 years because sex education has become more common. More public schools are willing to teach the subject. It surprises me constantly when I hear people say they don’t believe statistics like this. It saddens me that public school teachers are being bullied out of teaching what kids need to know. One principal told me that it was not the information I was teaching that he didn’t like — it was my style of teaching. In that moment, I learned that my style was what made me such a successful teacher. My husband, a psychologist, said that evening at dinner that the only person who wouldn’t like me is someone I had stood up to. That was the night I began to write my book for teachers on how to teach sex education.

What’s the role of parents in teaching kids about sex? Very simply, tell them what they want to know because they will tell you. Have a good relationship with your child and answer questions in a way that invites more questions. It’s false to believe that too much information stimulates sexual behavior. Research has proven over and over that’s not true. The guiding point should be that we should not be ashamed to ask questions about our bodies and explore our bodies.

Most sex educators fail to talk about the most obvious point of sex — pleasure. That’s sad because that’s the hook with kids. I would always talk about the three S’s of pleasure — sensitivity, slow, sensual. This included holding hands and kissing. I got more calls to the principal’s office for that than anything. But if they understand that you’re being transparent about sex, they’ll pay closer attention to other aspects of sex education. Parents and educators should say that want kids to be safe and enjoy sexual pleasure in a loving context in a long-term relationship.

My TCU connections are so important to me, and I’ve learned to make time for them and make them special. Now that we keep in touch with people through social media, it is so much easier to maintain relationships throughout the decades. I realize it is unusual to have annual reunions with your Greek friends, but my Delta Gamma pledge class has made it a priority to see each other once a year. When we started this practice, we didn’t have money or email technology. I wrote a letter each March to all the sisters stating where and when we would meet, and then we wrote it on our calendars and showed up. The first reunion was in 1971. One year we asked TCU Housing to put us up in the DG House in the same rooms with the same roommates we had when we were in college in the ’60s.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Alumni, Features

CHEW to the Rescue

A desire to help dogs led Leigh Owen Sendra to launch a nonprofit veterinary clinic.

Alumni, Features

Finding a Fit

A Neeley alum matches workers on the autism spectrum to high-tech careers.