Forensic invention

TCU engineering students build a bone-processing machine to speed up the extraction of DNA from human remains.

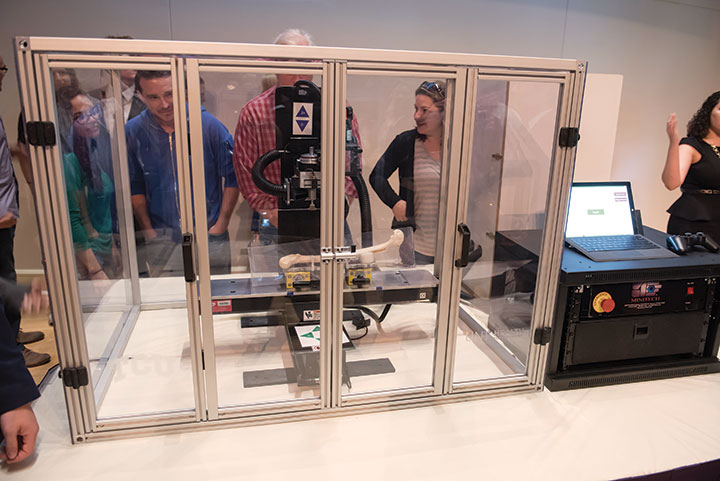

TCU Engineering students devised an automated bone-processing machine to make cutting and cleaning bone samples more efficient. (Photo by Glen E. Ellman)

Forensic invention

TCU engineering students build a bone-processing machine to speed up the extraction of DNA from human remains.

Scientists make precise cuts to remove a tiny piece of bone, crush it to powder and extract DNA. The meticulous work helps identify human remains.

The experts at the University of North Texas Health Science Center attempt to identify a corpse using high-powered bone saws, a process that generates a lot of bone dust.

“We have to clean and clean and clean,” said Rhonda Roby, a DNA expert, explaining that the practice prevents the carrying over of bone matter from sample to sample.

All the cleaning takes valuable time — and just a handful of labs exist to identify thousands of unknown bones. The health science center in Fort Worth is home to the world-renowned Center for Human Identification. Law enforcement agencies send unidentified remains every day for DNA testing.

But thousands of unidentified bone sets line shelves waiting for processing, said Tristan Tayag, professor of electrical engineering at TCU. “The bottleneck is the cleaning and extracting of the bone sample,” he said. “It is time-consuming because it is done manually.”

Tayag and Roby joined forces in 2014 and 2015 to create an automated bone-processing machine to reduce those cleaning and cutting times. “[The machine] was something that was stirring in my head,” said Roby, who came up with the idea about five years ago.

The Automated Bone Processing Machine was unveiled in May during a presentation at the College of Science and Engineering. Health science center researchers invented and designed the machine, and TCU engineering students built it.

“It was very cool,” said Dustin Jones, a senior mechanical engineering major, who worked on the project. “It was a great experience.”

Twenty-one undergraduate students worked in four different groups to build and test the cutting, cleaning, mounting and software for the machine. They customized a computer-controlled commercial tabletop mill to meet the forensic needs, using a PlayStation3 handset as the controller. The project, which required 210 hours of testing, was funded with about $40,000 from the health science center and a private gift.

“I feel great about the project,” said Michael George, project manager and a senior engineering major. “We created a solid system [that] should be easy for a new user to operate. It increases user safety while reducing the overall time it takes to obtain a bone sample.”

Roby said the machine will be patented, but there isn’t a high demand for it because there are so few identification labs. “This is clearly a very big first step for us,” said the former health science center faculty member who is now a professor at the J. Craig Venter Institute in California and heads the forensic genomics team at Human Longevity, Inc.

Roby, a well-known expert in her field, helped identify human remains after the 1973 Pinochet military coup in Chile, the 1993 Branch Davidian fire in Waco and the September 2001 attacks at the World Trade Center.

Andrea Hein ’13 contributed to this report.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Campus News: Alma Matters

From Application to Admission

Amid an increasingly selective admission process, Heath Einstein leads the team that builds the TCU community of the future.

Campus News: Alma Matters

From the Chancellor

Chancellor Victor J. Boschini, Jr., identifies what made TCU and its sesquicentennial so memorable.